Y BAE, Storiel, Bangor 2021

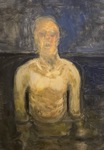

"Gorwel" (Horizon) Oil on Canvas, 73cm x 63cm. (Privately Owned)

Y BAE / EXHIBITING DURING LOCKDOWN - WALES ARTS REVIEW 1.4.21

Following the postponement of his solo exhibition Y BAE, Pete Jones reflects on the fluid nature of creating art during a pandemic and how his collection draws personal and cultural inspiration from his childhood in Hirael, Bangor.

My next solo exhibition of paintings was set to take place in the Storiel Gallery, Bangor during early 2020. Like so many events, the world-wide pandemic has made it necessary to re-schedule and the show is now due to begin during September 2021. Similar to my previous solo show at Oriel Ynys Mon during 2019, there is a large autobiographical element to the paintings. The show is entitled “Y BAE” (The Bay) and is an exploration of the area in which I grew up, the Hirael area of Bangor.

I wanted to explore the context in which this new collection of work is being prepared. As an artist I begin with feelings about a theme, person or place. The process of painting can be all consuming and sometimes takes some work in directions that I had not planned, “accidents” and “chance” are important. I think that I generally try to create a “visual ambience”, a feeling for a place rather than a photographic reproduction of what is before me. This has led to some of my recent work becoming more abstract in form. I have also started to experiment with sound and film.

Hirael Bay was made from sea and slate. The maritime and slate industries were the foundations for its development during the 19th and early twentieth centuries. Penrhyn dock was once the biggest slate port in the world. The community of Hirael was a proud one, all the world was there…. Sailors, Pious chapel goers, Drinkers, Composers, ship builders, poets, slate splitters, fighters, foundry workers, saints and sinners. I grew up in Hirael during the 1970s, a time by which much of the industry had gone. Looking back there was quite a bit of what could be described as dereliction. Our playgrounds included empty houses and half-demolished streets, disused military huts “on Beach” and the old foundry. Music was important to us, the dominant beats in Foundry Street, were Northern Soul and Motown.

The smell of the sea (and mud during hot summers) was strong and a reminder of our proximity to the deep. Hirael has always been prone to flooding from the sea. Large parts of Hirael are below sea level and its people have lived through many a deluge over the years. The council used to issue sandbags for us to place in doorways. I remember the feeling of dread whilst watching levels rise outside our backdoor – these feelings inspired the painting “Breuddwyd am storm yn Bae Hirael” (Dream about a storm in Hirael Bay).

The bay is tidal, when the sea is out a large expanse of mud is laid bare, brown and smooth apart from the area that is the site of the skeletal wreck of a boat. When I was a child, the “ribs” of the boat stood proud, and I often fantasised that it was the remains of an old Viking ship (it wasn’t). Little remains of the vessel these days, perhaps a metaphor for the area itself.

Football was a major activity during my childhood. The main street game was “10 lives“ which was played against any wall. There was a team of older lads, including my brother, called Bangor Dynamo, my first football heroes. There was a pecking order with local football – the younger lads always wanted to play with the older ones, but it was a “closed -shop”. When they actually allowed you to join in with them, due to lack of players (or willing goalkeepers) or some other reason, you felt ten feet tall. Most games took place “on beach”, a football field directly overlooking the sea, a sea into which many balls were lost. During hot summer evenings curlews would call from the mud and large groups of boys would play football on the edge of the sea. It was here that I would often gaze out at the horizon and wonder what was beyond it. Whilst at school I recall reading about an artist who stated that the sea was a “symbol of the infinite” (Monet, I think, but my memory fails). Whoever that was, that assertion was something that resonated greatly with me and has stuck with me throughout my life. Horizons play a prominent role in the show for example “Y Gorwel bell” (The far horizon) and “Gorwel ” (Horizon), the latter image being almost reduced to abstraction.

At the Northerly point of Hirael Bay lies the Garth area and its Victorian pier. The Pier was an important feature in my childhood. I remember walking on the pier as a small boy and seeing the green sea fall and rise between the cracks of the boards. I remember squeezing mam’s hand as tightly as I could, afraid that I would fall through those cracks. I would later spend many summer evenings trying to catch mackerel or “flatties” with the other lads, it was a fun place to be.

As I get older, the pier, now with its memorial benches, nameplates and bouquets feels more like a place of remembrance. My painting “Hiraeth” has attempted to capture the essence of that feeling, featuring a roughly painted bouquet of dying roses blowing away in the wind. Whilst undertaking the work for this exhibition a gamut of feelings have driven the work (hopefully without being overly sentimental). Cezanne, I think, once suggested that a work of art that did not begin in emotion is not art and I take comfort from that.

Whilst the process of painting has continued, I have also ventured into film making, creating a short piece which reflects this context in which the work has been created. Two cultural reference points have been important to me in this process, the poems of local man T. Llewelyn Williams who wrote about his own life in Hirael, and a series of photographic portraits of the people of Hirael taken by photographer Garry Stuart during the mid-70s. Garry took these images whilst a contemporary of the film director Danny Boyle during his time at Bangor university. These bodies of work have impressed me over the years and have encapsulated much of what I feel for the area. Some of their work features in the short film that I have made to show at the exhibition. Also included within the film is my own “soundscape”. Whilst not a musician my adolescence during the punk era gave me the confidence to experiment with music, an approach which probably leads to my attitude towards painting in so far as I am not precious about my work. I have been experimenting with ambient electronic sound and hope that the results compliment the imagery presented within the film.

The extended lead into the exhibition due to the pandemic has meant that much of the original work has been discarded and new work created. As I am not precious about my paintings I will often paint over “finished” works. With several months left before the exhibition it may be that the final work for it has not yet been created.

"Y Bae" Storiel Gallery, Bangor

9th of October, 2021 - Friday 31st December, 2021.

Y BAE - A short film accompanying the exhibition - Storiel 2021

So as to add more context to the paintings I made a short film which was shown on a loop at the exhibition. Within the film are two important cutural reference points for me. Firstly, the poems of Hirael man T. Llewelyn Willams, who captured much of what I feel through his words. In the film I read one of his poems "Hirael Vanished Sea Village" and I am extremely grateful to his daughter for allowing me permission to use his work. The second important cultural source to me are the series of photographs taken by Garry Stuart of the people of Hirael during the 1970s. Again I am so grateful to Garry for his permission to use some of his beautiful images (Link below).

WALES ARTS REVIEW 6-12-21

James Lloyd finds presence through absence in in Pete Jones’ exhibition,

THE BAY, showing at Storiel, Bangor.

A sense of loss and longing appears as a veil through which we see the subject of Pete Jones’ oil paintings, the Hirael bay in Bangor; its tidal bays, infinite ocean horizons and the faces of those who lived there. THE BAY exhibition at Storiel Bangor explores Jones’ recollections of this area in which he grew up, of what was and is now gone, but also a symbolic sense of change and renewal. There is the presence of people in the exhibition, yet they seem disconnected from the Hirael bay itself. In Codi’r cregyn gleision, the sun makes white the gunwale of the fishing boat, silhouetting the day’s catch. The fisherman is facing away, yellow jacket muted in shadow. It’s a beautiful painting, the first that caught my eye as I entered the exhibition. Like many of Jones’ paintings, it’s the stark contrasts between light and dark with flashes of colour that make them so striking. The whiteness of the light empties it of any warmth, a dying light that emotes the painting. Two nets of fish hang from a crane over the water; a good haul, yet there is no sense of celebration or victory. Like all the paintings, there is a soft focus, in this painting it seems to be from the sea spray and mist, that gives the sense of a faded memory. It gives the paintings this distance, as though what we see is out of reach.

The portraits of local faces also have this same effect. Figures fade into the darkness behind them, their expressions flat, their eyes sunken and hollow. Only The Last Mariner retains some glistening of the sea in his eye, a sea he is now removed from. The portraits are the fading memories of people who have passed on in some form, faces now detached from the place and fading into obscurity.

The sea is the real focus of this exhibition, the water that enabled Hirael Bay to have once been the largest slate port in the world. Every painting of its flat plain of ocean and distant horizon displays a different sunrise or sunset. Every painting shows a constantly changing landscape and emotion. In The Spilled Blood and the Wild Sky, a bright red horizon deepens into night, a hidden sun casts a fading reflection on a dark sea. Its bold use of red makes the painting visually arresting, in combination with its gold frame too pulls at something in me, I’m not sure what. There are nightscapes too, such as the white moon reflected back off the sea in Lleuad. This piece made me think of a comment by Van Gogh, that ‘the night is more alive and more richly coloured than the day.’ The stark white moon on the dark blues and greens of night is captivating. The painting is small, 46cx46cm, yet it draws you to its mystery and peace. Out alone in the dark while everyone else is inside, it can feel as though the moon shines only for you.

In Sgerbwd, the bay takes on the deep orange of sunset. In the foreground, the carcass of a boat on the flowered shore gives the painting a deep sense of loss and decay, a sentiment apparent in the similar Detritus and a theme that runs through the exhibition. As Pete Jones describes them as the ‘ribs’ of an old boat, the composition and subject reminded me of Gustave Guillamet’s desert painting Le Sahara, which depicts an animal carcass against an infinitude of desert. In Guillamet’s painting, an approaching group on the horizon cast long silhouettes across the desert, and similarly too in Sgerbwd the flowers seemingly growing from the carcass of the boat give the painting a sense of renewal from decay. Birds flash white against a pink sky in Hogia Hirael. The symbolic rising and setting of the sun, the transition between day and night in almost all of Jones’ paintings gives them the sense of constant change. The past is left to decay, but each day brings a new and unique beauty. In Mordaith, a pale sun slowly illuminates white clouds from a grey dawn over a calm hazy sea. The night still lingers, dark blue in the top of the frame, the sickle moon still lingering. Looking The way Pete Jones paints is as though to see these landscapes, seascapes and people through a veil. A veil of loss and longing distorts the image, as though recalling a clouded memory written into the landscape, present in its absence. Yet there is hope too, a reassurance found in the sun rising and setting, the tides ebbing and flowing. As Pete Jones says, Monet saw the sea as a ‘symbol of the infinite.’ Perhaps of infinite space and far horizons, but also of constant change and renewal. The sun sets in Pete Jones’ paintings, but it also rises.

"Lleuad" (Moon) Oil on Canvas 46cm x 46cm. (Privately owned)

Selected paintings from the "Y Bae" exhibition at Storiel, Bangor 2021.

Ffilm fer wedi ei gwneud fel moliant i fy mhlentyndod yn Hirael.

Maen cynnwys lleoedd a oedd yn bwysig i mi a hunanbortread diweddar. Roedd "10 Lives" yn gêm lle gwnaethoch chi gicio pêl yn erbyn rhan o unrhyw wal.

Bob tro roeddech yn fethu y rhan fe golloch chi fywyd.

Short film made as a eulogy to my childhood in Hirael.

It features places that were important to me and a recent self-portrait."10 Lives" was a game in which you kicked a ball against an area of any wall.

Each time you missed the area you lost a life.

"Ghostships" - Oil on board

This painting was inspired by imagined visions of the historic Slate Ships of Hirael Bay - I was completely humbled that the composer Cameron Biles-Liddell composed a piece of music "Apparitions of Light" based upon this painting for the "Annwn" exhibition at Wrexham 2021, which featured the painting. Below is a link to a performane of the piece, "Apparitions of Light" performed by Benjamin Powell