Exhibitions

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

Wrexham Museum 2015

Storiel, Bangor 2016

Ceredigion Museum, Aberystwyth 2016

Storiel, Bangor 2017

Bangor Arts Initiative Gallery 2017

Plas Glyn y Weddw 2018

Royal Cambrian Academy, Conwy 2018

Plas Glyn y Weddw 2019

Ty Pawb, Wrexham 2021

"FREEDOM - Europe - Without boundaries?" - Soest, Germany 2022

"Human Bridges" - Storiel, Bangor 2023

"Cyfoes" Gregynog Gallery, National Library of Wales 2023/24

Plas Glyn y Weddw 2024 (Joint show with Louise Morgan RCA)

"Hand for Life" Bürgerzentrum, Herzberg, Germany 2025

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

"Môr" - Venue Cymru, Llandudno 2018

"Mordaith" - Oriel Ynys Môn 2019

"Afon" - Neuadd Ogwen, Bethesda 2020

"Y Bae" - Storiel, Bangor 2021

"Cynefin" Oriel Ynys Môn 2025

MORDAITH - Oriel Ynys Môn 2019

My first major solo exhibiton took place at Oriel Ynys Môn during 2019. This included over 70 pieces of work and was kindly supported by the Arts Council of Wales. Prior to the event, Wales Arts Review published my short essay on the background to the exhibition and the autobiographical nature of the show. I am grateful to Wales Arts Review for considering this show to be amongst the top 10 visual arts exhibitions in Wales for 2019.

"MORDAITH - The paintings of Pete Jones" (Wales Arts Review 29.5.19)

For thirty five years, Pete Jones worked in the NHS as a learning disability nurse, unable to fulfil his ambition of becoming a full-time painter. Now, on the eve of his first ever solo exhibition, at Oriel Ynys Môn on Anglesey, Pete reflects on his journey, and his new artistic vision.

This June I will be holding my first major solo exhibition as a painter. Perhaps, oddly for a first show, it will be a retrospective in the sense that this is my first opportunity to reflect on my life and to explore the themes and imagery that have affected and influenced me over the past 58 years.

I spent my formative years in Hirael, a small, closely-knit area of Bangor with a rich maritime and industrial heritage linked to the Slate industry. Rows upon rows of council housing in a post-industrial community, typical of many other such areas around Wales. On leaving school I completed a degree in Fine Art at Loughborough College of Art & Design (Via Chester School of Art). On leaving Art College in 1983 I set about getting a life. Sadly for me “Life”, post-art college, consisted of rejected applications to undertake a Masters Degree from some of the finest institutions in the land and a twelve month stretch of unemployment in the East Midlands of England, a working-class “gap year” if you will.

During 1985 I returned home to Bangor, broke and looking for work. There followed some diverse, but short-term, employment as a Council labourer, Hospital Porter and Graphic Artist at the Welsh National Centre for Religious Education (the latter being quite a challenge for an atheist). During 1986 I enrolled to become a “Registered Nurse for the Mentally handicapped” as it was termed at the time. The training was based at Bryn-y-Neuadd Hospital at Llanfairfechan, just a few miles outside of Bangor. The reason for this swerve into the NHS still eludes me. I think I had a vague notion of wanting to become an Art Therapist and thought that this experience would help (It didn’t).

During the next few years I worked supporting adults labelled as having “learning disabilities and challenging behaviour”. Many individuals had mental health issues, sensory needs, physical-ill health and sometimes, profound physical impairments. Much of the challenges stemmed from a system and environment that wasn’t designed to respect the individual needs of human beings and were built around Victorian attitudes to power and control.

On becoming a nurse I remember thinking that I would have to forget any artistic ambitions that I previously had and focus completely on supporting the individuals I was working with. Having said that my interest in painting and painters had been a major theme in my life and was not something I could clear out of my memory bank easily.

An incident that was psychologically pivotal in terms of my future artwork, occurred whilst I was supporting a gentleman to have a bath in one of the cold, white-tiled, bathrooms at the hospital. Having just been washed, the usual routine was to lift him onto the adjacent medical examination couch so that he could be dried more effectively (his body was quite misshapen due to a serious physical condition). Having helped him on to the couch I went for some towels from a nearby cabinet and turned back towards him. It was at this point that the visual imagery of what was before me completely jarred my senses. It was as if I was standing in front of a painting by Francis Bacon. The isolated figure and warm flesh tones of a human being lying on a type of visual stage, with the cold structured surface of a large, tiled wall behind was the very format for one of Bacon’s works. This experience led me to start storing visual memories of the people I got to know and the situations I saw on a daily basis. I knew that I wanted to use this information to inform my future painting so these images went into my, now re-energised, memory bank.

Whilst I had undertaken sporadic painting commissions during my time as a nurse, these were limited due to working full-time and raising a family with my wife Anna (also a nurse).

Since my retirement from Nursing in 2016 I have returned to my primary ambition to become an accomplished painter. Much of my work in the past 3 years has reflected my experience of working in the Hospital, with individual portraits featuring heavily. Much of this work was based upon archive photographs and my own visual memory. I think it was Rembrandt who suggested that life etches itself onto faces showing our violence, excesses or kindnesses. Within such a context I have tried to capture the humanity and integrity of some of the people who lived (and died) in the hospital, many without families, and whose very existence would have been unknown to many. I was fortunate that one of my portraits “Joseph Roy Bevans” is now in the collection of the National Library of Wales and will be loaned for the exhibition. This painting also featured in a short film by Paul Hunt, “A Hidden Portrait” which was shown on BBC2 Wales last year.

This exhibition is an illustration of my own life through a range of themes including disability, mental health, identity, mortality, loss and yearning (“Hiraeth”). The backdrop for this work is the physical and cultural environment of Wales. Important reference points are people I have known whose lives took very different “voyages” to my own. The titles of some of the paintings, I hope, add an extra dimension to the imagery.“Satellite of love”, “Moonage Daydream” and “Love will tear us apart” reflect the importance of music in my life over the years. There are also pieces that explore notions of Welsh cultural identity e.g. “Capel Celyn” and “Cadair Longshanks”.

Painting can be a powerful vehicle for conveying ideas and feelings. I think that it is fundamentally important that painting either makes people think something or feel something and that exceptional painting can do both. This exhibition is very personal to me and I certainly feel, like many artists, that there will be an element of me bearing my soul to the public. I hope that the diversity of themes and imagery will resonate with people who come to the show.

"Y BAE" Storiel, Bangor, 2021

“The Bay” is an exploration of the area in which I grew up, the Hirael area of Bangor, an area shaped by sea and slate. The smell of the sea (and mud during hot summers) was strong and a reminder of our proximity to the deep. At high tide, large parts of Hirael are below sea level and under threat of flooding. A range of emotional and cultural refence points have guided the work. Recollections of looking out to sea and the horizon feature prominently in this body of work. I have attempted to create atmospheres which reflect my feelings for what was and is now gone.

Y BAE / EXHIBITING DURING LOCKDOWN - WALES ARTS REVIEW 1.4.21

Following the postponement of his solo exhibition Y BAE, Pete Jones reflects on the fluid nature of creating art during a pandemic and how his collection draws personal and cultural inspiration from his childhood in Hirael, Bangor.

My next solo exhibition of paintings was set to take place in the Storiel Gallery, Bangor during early 2020. Like so many events, the world-wide pandemic has made it necessary to re-schedule and the show is now due to begin during September 2021. Similar to my previous solo show at Oriel Ynys Mon during 2019, there is a large autobiographical element to the paintings. The show is entitled “Y BAE” (The Bay) and is an exploration of the area in which I grew up, the Hirael area of Bangor.

I wanted to explore the context in which this new collection of work is being prepared. As an artist I begin with feelings about a theme, person or place. The process of painting can be all consuming and sometimes takes some work in directions that I had not planned, “accidents” and “chance” are important. I think that I generally try to create a “visual ambience”, a feeling for a place rather than a photographic reproduction of what is before me. This has led to some of my recent work becoming more abstract in form. I have also started to experiment with sound and film.

Hirael Bay was made from sea and slate. The maritime and slate industries were the foundations for its development during the 19th and early twentieth centuries. Penrhyn dock was once the biggest slate port in the world. The community of Hirael was a proud one, all the world was there…. Sailors, Pious chapel goers, Drinkers, Composers, ship builders, poets, slate splitters, fighters, foundry workers, saints and sinners. I grew up in Hirael during the 1970s, a time by which much of the industry had gone. Looking back there was quite a bit of what could be described as dereliction. Our playgrounds included empty houses and half-demolished streets, disused military huts “on Beach” and the old foundry. Music was important to us, the dominant beats in Foundry Street, were Northern Soul and Motown.

The smell of the sea (and mud during hot summers) was strong and a reminder of our proximity to the deep. Hirael has always been prone to flooding from the sea. Large parts of Hirael are below sea level and its people have lived through many a deluge over the years. The council used to issue sandbags for us to place in doorways. I remember the feeling of dread whilst watching levels rise outside our backdoor – these feelings inspired the painting “Breuddwyd am storm yn Bae Hirael” (Dream about a storm in Hirael Bay).

The bay is tidal, when the sea is out a large expanse of mud is laid bare, brown and smooth apart from the area that is the site of the skeletal wreck of a boat. When I was a child, the “ribs” of the boat stood proud, and I often fantasised that it was the remains of an old Viking ship (it wasn’t). Little remains of the vessel these days, perhaps a metaphor for the area itself.

Football was a major activity during my childhood. The main street game was “10 lives“ which was played against any wall. There was a team of older lads, including my brother, called Bangor Dynamo, my first football heroes. There was a pecking order with local football – the younger lads always wanted to play with the older ones, but it was a “closed -shop”. When they actually allowed you to join in with them, due to lack of players (or willing goalkeepers) or some other reason, you felt ten feet tall. Most games took place “on beach”, a football field directly overlooking the sea, a sea into which many balls were lost. During hot summer evenings curlews would call from the mud and large groups of boys would play football on the edge of the sea. It was here that I would often gaze out at the horizon and wonder what was beyond it. Whilst at school I recall reading about an artist who stated that the sea was a “symbol of the infinite” (Monet, I think, but my memory fails). Whoever that was, that assertion was something that resonated greatly with me and has stuck with me throughout my life. Horizons play a prominent role in the show for example “Y Gorwel bell” (The far horizon) and “Gorwel ” (Horizon), the latter image being almost reduced to abstraction.

At the Northerly point of Hirael Bay lies the Garth area and its Victorian pier. The Pier was an important feature in my childhood. I remember walking on the pier as a small boy and seeing the green sea fall and rise between the cracks of the boards. I remember squeezing mam’s hand as tightly as I could, afraid that I would fall through those cracks. I would later spend many summer evenings trying to catch mackerel or “flatties” with the other lads, it was a fun place to be.

As I get older, the pier, now with its memorial benches, nameplates and bouquets feels more like a place of remembrance. My painting “Hiraeth” has attempted to capture the essence of that feeling, featuring a roughly painted bouquet of dying roses blowing away in the wind. Whilst undertaking the work for this exhibition a gamut of feelings have driven the work (hopefully without being overly sentimental). Cezanne, I think, once suggested that a work of art that did not begin in emotion is not art and I take comfort from that.

Whilst the process of painting has continued, I have also ventured into film making, creating a short piece which reflects this context in which the work has been created. Two cultural reference points have been important to me in this process, the poems of local man T. Llewelyn Williams who wrote about his own life in Hirael, and a series of photographic portraits of the people of Hirael taken by photographer Garry Stuart during the mid-70s. Garry took these images whilst a contemporary of the film director Danny Boyle during his time at Bangor university. These bodies of work have impressed me over the years and have encapsulated much of what I feel for the area. Some of their work features in the short film that I have made to show at the exhibition. Also included within the film is my own “soundscape”. Whilst not a musician my adolescence during the punk era gave me the confidence to experiment with music, an approach which probably leads to my attitude towards painting in so far as I am not precious about my work. I have been experimenting with ambient electronic sound and hope that the results compliment the imagery presented within the film.

The extended lead into the exhibition due to the pandemic has meant that much of the original work has been discarded and new work created. As I am not precious about my paintings I will often paint over “finished” works. With several months left before the exhibition it may be that the final work for it has not yet been created.

WALES ARTS REVIEW 6-12-21

James Lloyd finds presence through absence in in Pete Jones’ exhibition,

THE BAY, showing at Storiel, Bangor.

A sense of loss and longing appears as a veil through which we see the subject of Pete Jones’ oil paintings, the Hirael bay in Bangor; its tidal bays, infinite ocean horizons and the faces of those who lived there. THE BAY exhibition at Storiel Bangor explores Jones’ recollections of this area in which he grew up, of what was and is now gone, but also a symbolic sense of change and renewal. There is the presence of people in the exhibition, yet they seem disconnected from the Hirael bay itself. In Codi’r cregyn gleision, the sun makes white the gunwale of the fishing boat, silhouetting the day’s catch. The fisherman is facing away, yellow jacket muted in shadow. It’s a beautiful painting, the first that caught my eye as I entered the exhibition. Like many of Jones’ paintings, it’s the stark contrasts between light and dark with flashes of colour that make them so striking. The whiteness of the light empties it of any warmth, a dying light that emotes the painting. Two nets of fish hang from a crane over the water; a good haul, yet there is no sense of celebration or victory. Like all the paintings, there is a soft focus, in this painting it seems to be from the sea spray and mist, that gives the sense of a faded memory. It gives the paintings this distance, as though what we see is out of reach.

The portraits of local faces also have this same effect. Figures fade into the darkness behind them, their expressions flat, their eyes sunken and hollow. Only The Last Mariner retains some glistening of the sea in his eye, a sea he is now removed from. The portraits are the fading memories of people who have passed on in some form, faces now detached from the place and fading into obscurity.

The sea is the real focus of this exhibition, the water that enabled Hirael Bay to have once been the largest slate port in the world. Every painting of its flat plain of ocean and distant horizon displays a different sunrise or sunset. Every painting shows a constantly changing landscape and emotion. In The Spilled Blood and the Wild Sky, a bright red horizon deepens into night, a hidden sun casts a fading reflection on a dark sea. Its bold use of red makes the painting visually arresting, in combination with its gold frame too pulls at something in me, I’m not sure what. There are nightscapes too, such as the white moon reflected back off the sea in Lleuad. This piece made me think of a comment by Van Gogh, that ‘the night is more alive and more richly coloured than the day.’ The stark white moon on the dark blues and greens of night is captivating. The painting is small, 46cx46cm, yet it draws you to its mystery and peace. Out alone in the dark while everyone else is inside, it can feel as though the moon shines only for you.

In Sgerbwd, the bay takes on the deep orange of sunset. In the foreground, the carcass of a boat on the flowered shore gives the painting a deep sense of loss and decay, a sentiment apparent in the similar Detritus and a theme that runs through the exhibition. As Pete Jones describes them as the ‘ribs’ of an old boat, the composition and subject reminded me of Gustave Guillamet’s desert painting Le Sahara, which depicts an animal carcass against an infinitude of desert. In Guillamet’s painting, an approaching group on the horizon cast long silhouettes across the desert, and similarly too in Sgerbwd the flowers seemingly growing from the carcass of the boat give the painting a sense of renewal from decay. Birds flash white against a pink sky in Hogia Hirael. The symbolic rising and setting of the sun, the transition between day and night in almost all of Jones’ paintings gives them the sense of constant change. The past is left to decay, but each day brings a new and unique beauty. In Mordaith, a pale sun slowly illuminates white clouds from a grey dawn over a calm hazy sea. The night still lingers, dark blue in the top of the frame, the sickle moon still lingering. Looking The way Pete Jones paints is as though to see these landscapes, seascapes and people through a veil. A veil of loss and longing distorts the image, as though recalling a clouded memory written into the landscape, present in its absence. Yet there is hope too, a reassurance found in the sun rising and setting, the tides ebbing and flowing. As Pete Jones says, Monet saw the sea as a ‘symbol of the infinite.’ Perhaps of infinite space and far horizons, but also of constant change and renewal. The sun sets in Pete Jones’ paintings, but it also rises.

TU HWNT I'R MYNYDDOEDD

Oriel Plas Glyn y Weddw 2024

TU HWNT I'R MYNYDDOEDD (BEYOND THE MOUNTAINS)

I have recently completed a series of paintings to show at Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw. “Beyond the Mountains” commences on Sunday13th October, 2024 and will run for three months until 24th December. This will be a joint exhibition with fellow Welsh Artist Louise Morgan RCA. My hope is that Louise’s striking landscapes will combine well with my own work.

I have been fortunate in recent years that several of my portraits have managed to make their way to the national collections of Wales in Aberystwyth and Cardiff but the focus of this body of work, rather than portraiture, will be the Mountains and Sea around North Western Wales.

Much of my time is spent up in the mountains or on the coast. When I am in these places, especially in more recent years, I have probably become more reflective in terms of my own awareness of our fragile mortality. These feelings become more acute when faced with the weathered grandeur of the land and seascapes of the Western Coast of Northern Wales, the context in which the work is set. Feelings are also compounded following the loss of family or friends. The solar and lunar cycles also feature heavily, themes that reflects the constant passage of time.

Painting can be a selfish endeavour, sometimes focusing upon inward responses to life, the exploration of ideas and the resolution of thoughts and personal feelings. For me it is an organic process that is greatly influenced by my own feelings in response to what I see and feel.

My paintings attempt to create a feel or “visual ambience” of a place rather than a detailed, pictorial representation of what is before me. My starting points for some of the works were the words of artists and writers that have resonated with me in terms of my own view of life and of Wales, these include Brenda Chamberlain, Patrick Jones and R.S. Thomas - Words can inspire imagery just as imagery can inspire words.

I have tried to work quickly and instinctively, Influenced by chance. Many of the paintings have thick layers of paint that have been re-worked several times and some retain the feint imagery of what lay beneath the final image. I have found this process interesting and I hope it has given an additional depth to the final work.

Pete Jones at Plas Glyn-y-Weddw:

A commentary on 6 paintings

Gavin Keeney

Northwest Wales has what I can only call a somatic effect on my body and mind. It has partly to do with my repeated visits since 2013, but it also has something to do with a mythic dimension in “time-space” that defies categorization. This was confirmed when I visited an exhibition at Plas Glyn-y-Weddw in Llanbedrog on October 29. The exhibition, featuring paintings by five artists, was billed as “A joint exhibition of landscape and figurative art inspired by Welsh poets, industrial and cultural heritage.” Yet, the part that drew my immediate attention was the work of Pete Jones, assembled under the title “Tu Hwnt i’r Mynyddoedd / Beyond the Mountains.” And, amidst several dozen paintings by Jones (forty-one to be precise), the part within the part that truly drew my attention was a “set” of six paintings of dark and sombre, luminous landscapes featuring “Sea + Sky.” The larger corpus of works was spread across three galleries, whereas this set of six paintings shared the wall of one gallery as if they were inseparable. All of the other works on view by Jones departed from the six luminous, nearly monochromatic works that focused on something in the landscape of Northwest Wales that spoke to that somatic effect “being in Northwest Wales” had on my body and mind.

The six paintings (all oil on canvas) were: Soul of the Sea (122x91cm); Under the Mountain Lake (61x51cm); Soul of the Mountain (122x91cm); “Bird on the Winter Sea” (61x51cm); Carnedd (61x51cm); and Y swnt (67x54cm). The press release (flyer) for “Tu Hwnt i’r Mynyddoedd / Beyond the Mountains” included a sequence of provocative statements regarding influences intended to set the work in that mythic reserve I suspected being responsible for my somatic reaction to Northwest Wales. The various statements included:

“The Mountains and Sea around Northwestern Wales”

“Loss of family and friends”

“Solar and lunar cycles also feature heavily”

“Themes that reflect the constant passage of time”

“‘Visual ambience’ of a place rather than a detailed, pictorial representation of what is before me”

“Words of artists and writers that have resonated with me in terms of my own view of life and of Wales”

“Words can inspire imagery just as imagery can inspire words”

Working “quickly and instinctively, influenced by chance”

Also playing in the main two galleries was what could only be called “ambient music,” composed by Jones. It, too, was entitled “Tu Hwnt i’r Mynyddoedd” (2024). Low enough in volume to be unobtrusive, it nonetheless added to the spell cast by that set of six paintings.

After several trips around the three galleries, to process what was on display, and following stepping outside to smoke once or twice, while gazing across rooftops toward Llanbedrog beach, Cardigan Bay, and the Irish Sea, I then sat “watching” the set of six paintings, the somber and luminous set, expecting them to start moving – the waves to roll, the skies to part, to reveal their secrets. They shared not only somber luminosity but also a depth. The depths extended in some “into the sea” and in others “into the sky” … In some “into both” (sea + sky). In others, “Sea + Sky” were one thing – a totality – horizon present or horizon absent. In the set of six, landscape itself (mountains, shoreline, lake, sea, sky, sun/moon, treeline) receded as luminous horizon or luminous clouds leapt forth. In one of the set of six (Soul of the Mountain), at “stage left” (top left corner), a moon or sun rose/set/fell, appearing to draw with it a torrent of atmospheric chaos (clouds, mist, winged hallucinatory serpents or …). It all “fell” (was falling) into place/not-place, earth and sky “One” ancient urn of infernal and celestial fires.

One outtake so to speak from the set of six was an exceptionally intense and smallish canvas entitled “Blood and the Wild Sky” (oil on canvas, 76x50cm). It was in reference to a passage in “Welsh Landscape,” a poem by R.S. Thomas. The passage referenced was:

“To live in Wales is to be conscious

At dusk of the spilled blood

That went into the making of the wild sky …”

The “bloody canvas” (image of turbulent sea/sky, distant/setting sun/moon in a patch of golden-yellow amidst blood-red sea/sky) overflowed the canvas, spilling on to the white wooden frame, with a few bloody fingerprints for good measure. (It would have been additionally provocative if Jones had left some bloody fingerprints on the gallery wall, the artwork then truly entering into dialogue with the room …) Traces of human figures behind the sea/skyscape were barely discernible or “not there” at all – hallucinations inferred or hallucinations incurred.

Jones somehow managed to tap into that “somatic” effect (affective and/or mythic reserve) of the Welsh landscape I felt upon arrival, upon all arrivals in Northwest Wales since my first arrival in 2013; an affective register in landscape that spoke to me of various things, but foremost of “Sea + Sky” as selfsame register, at some level, of “Fate + Grace.”

Gavin Keeney is a New York based author, editor and critic. He is also Director of "Edition One", a literary agency for artists ans scholars. This piece is from his "Substack" page published 30/10/24.

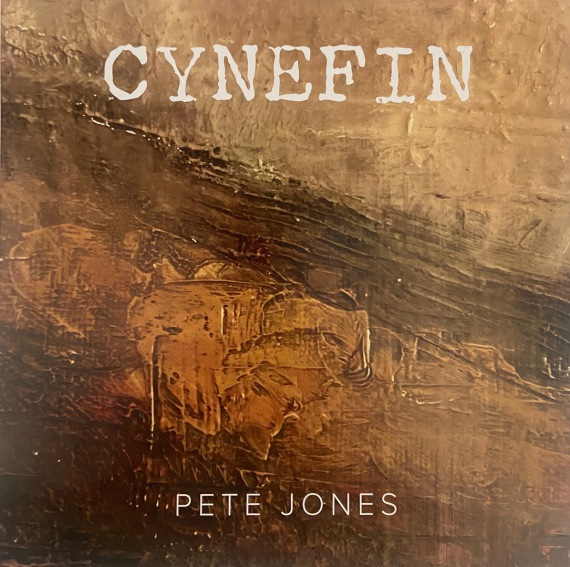

"CYNEFIN" Oriel Ynys Môn 2025

This exhibition was a personal exploration of the concept of “Cynefin”. It featured 117 paintings and drawings completed in 1979 through to newly completed work. As well as figurative landscape and portraits, more symbolic work was also included. It was a personal response and reflection on the experiences, people and places that have had an emotional impact upon me throughout my life.